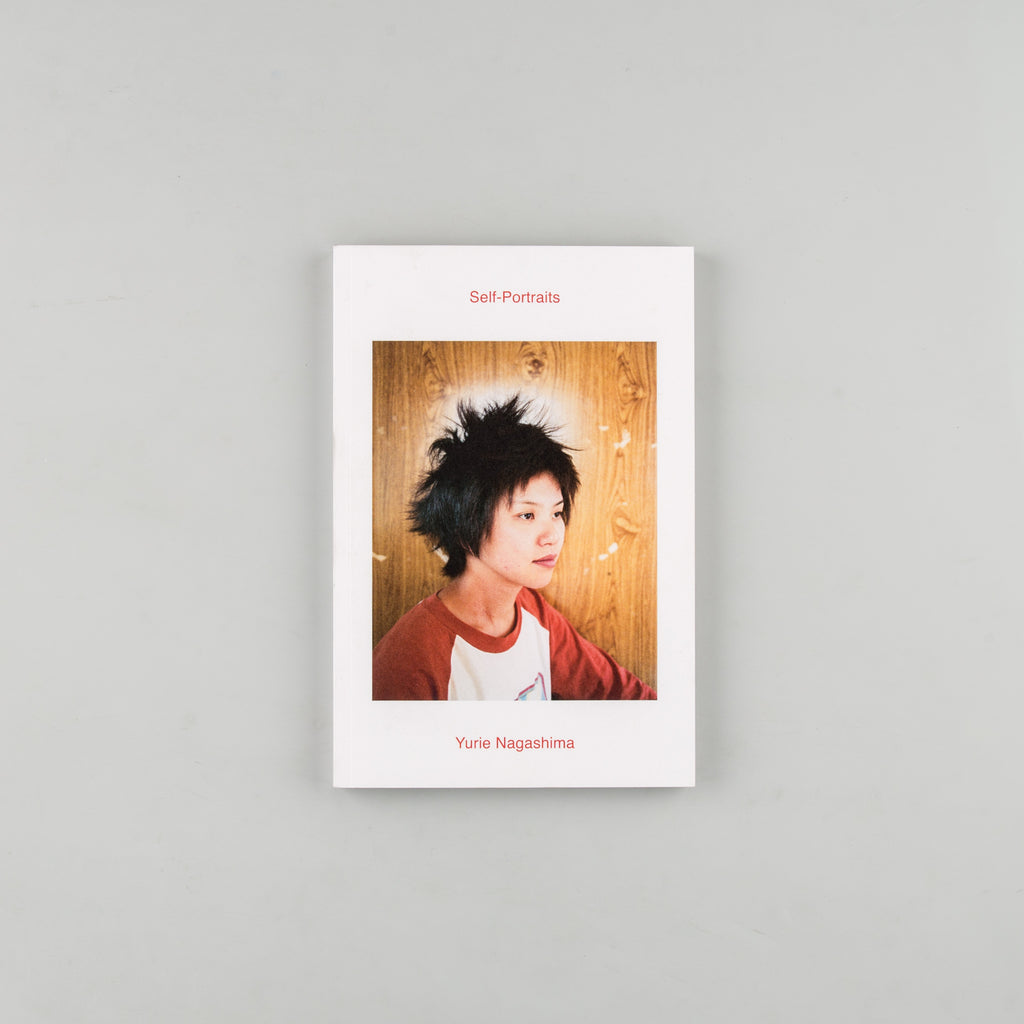

Self-Portraits

Yurie Nagashima

£25.00

Shown originally as a 30-minute slideshow of over 600 images as part of Nagashima’s survey exhibition And a Pinch of Irony with a Hint of Love at Tokyo Photographic Art Museum in 2017, Self-Portraits by Yurie Nagashima charts the evolution of this major female artist over a period of 24... Read More

Shown originally as a 30-minute slideshow of over 600 images as part of Nagashima’s survey exhibition And a Pinch of Irony with a Hint of Love at Tokyo Photographic Art Museum in 2017, Self-Portraits by Yurie Nagashima charts the evolution of this major female artist over a period of 24 years from 1992-2016.

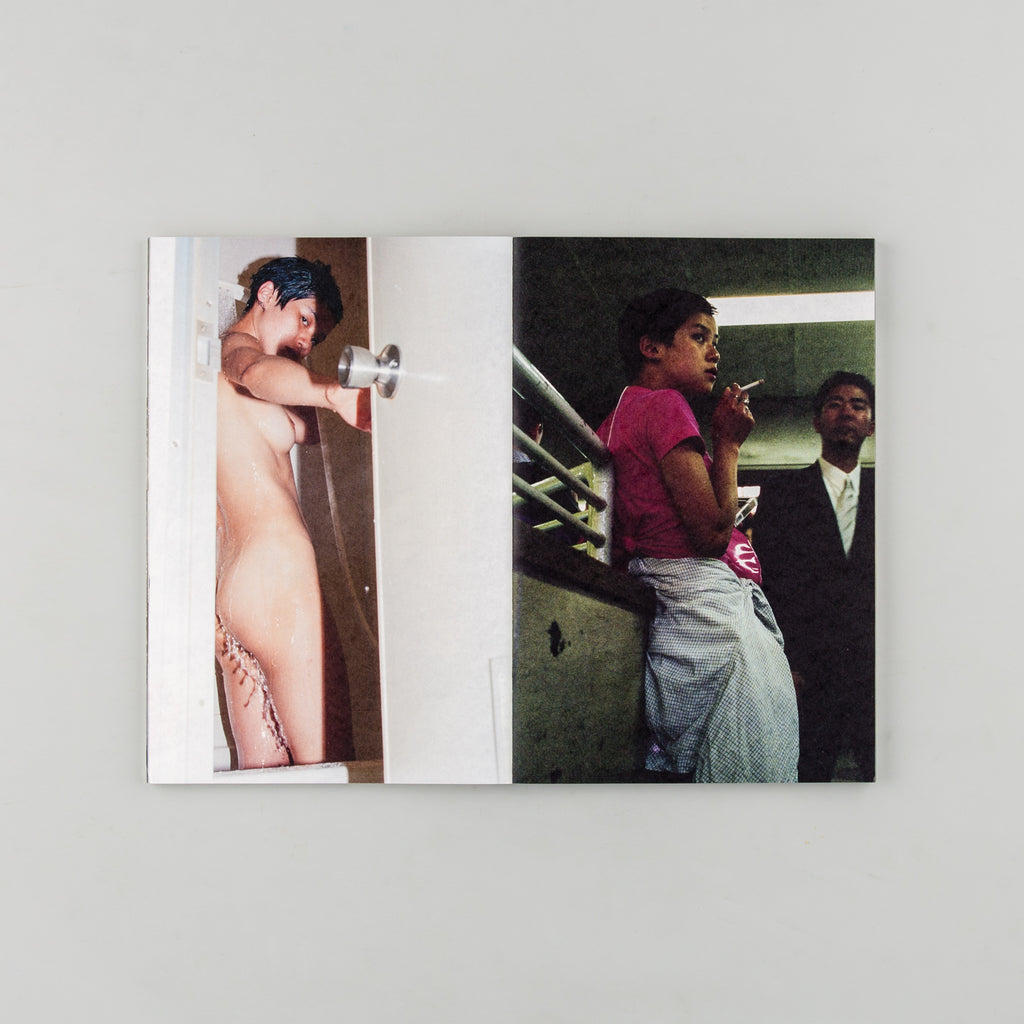

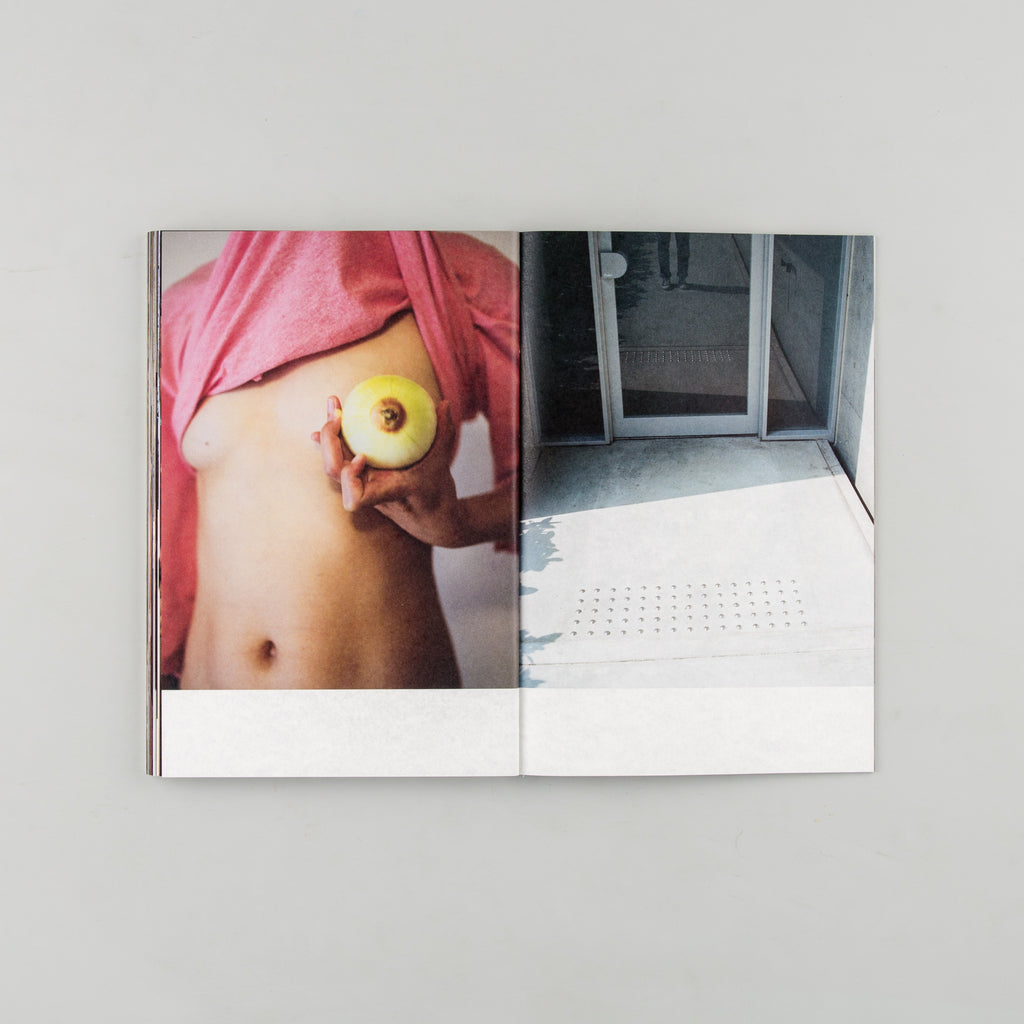

The opening photograph taken while on a backpacking trip is closely followed by her early, much publicized, self-portrait nudes; scenes amongst her peers in Tokyo in the mid-90s through her studies abroad at CalArts in Los Angeles. Returning to Tokyo in 1999 she continued to take self-portraits through her pregnancy, the birth of her son and on during the proceeding years of maturing and motherhood.

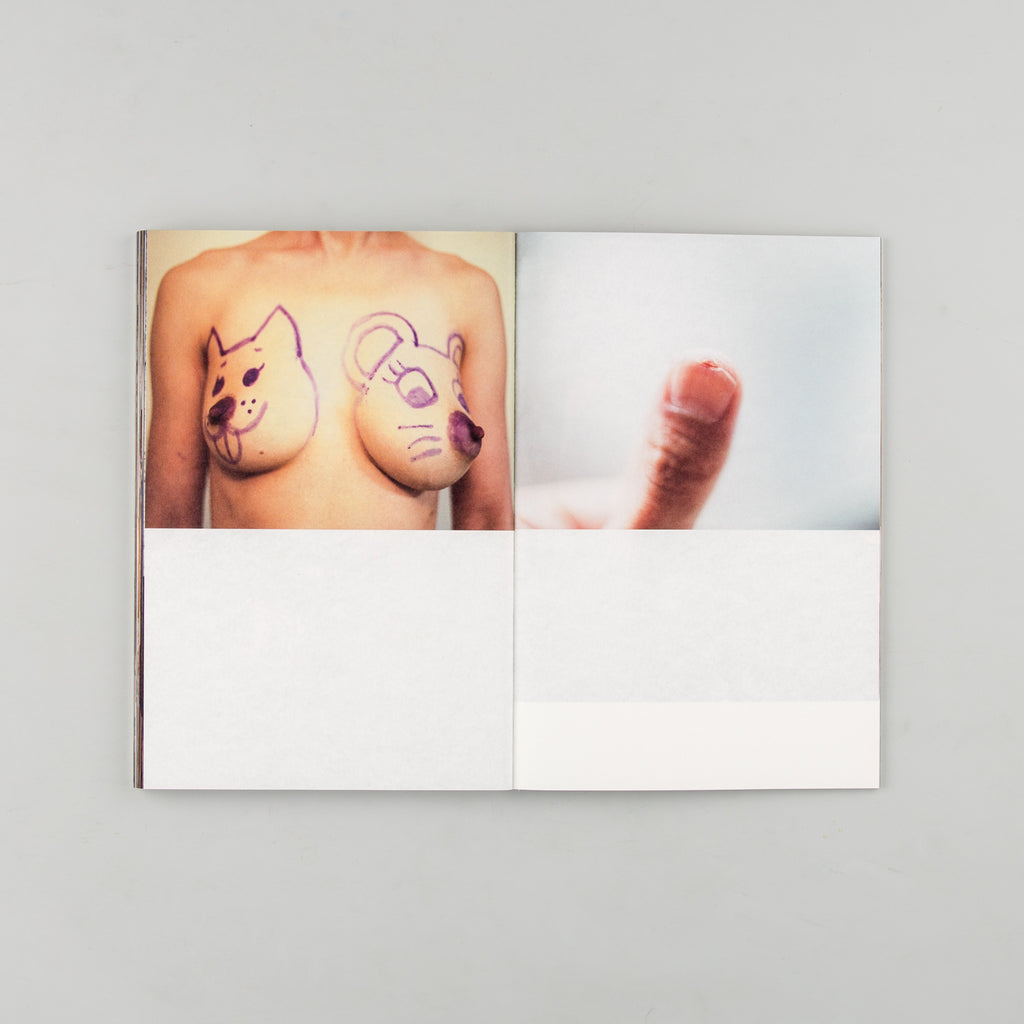

From a conversation with Lesley A. Martin, Aperture Foundation’s Creative Director, in the introduction Nagashima talks about her early self-portraits as a form of activism, that by creating a parody of self-portrait pin-ups she found “a way of talking about how the gaze of male society works on the female body.” She goes on “I was angry at the Hair Nude boom, and thought, “Okay, there’s no way men can use and consume a female body for their own agenda” literally claiming the agency of images of her own body on her own terms. “I realized that self-portraiture is an important genre of photography, especially in the context of feminism…. The self-portrait means that you can take on both roles, as a model and as a photographer. When you have a camera on a tripod, you have the space in front of the camera and also the space behind the camera. It’s very symbolic. It’s a way of taking action against the historical roles of the male and female in photography.” While the early work is clearly performative in this way as the sequence moves on, it seems to get more personal and diaristic.

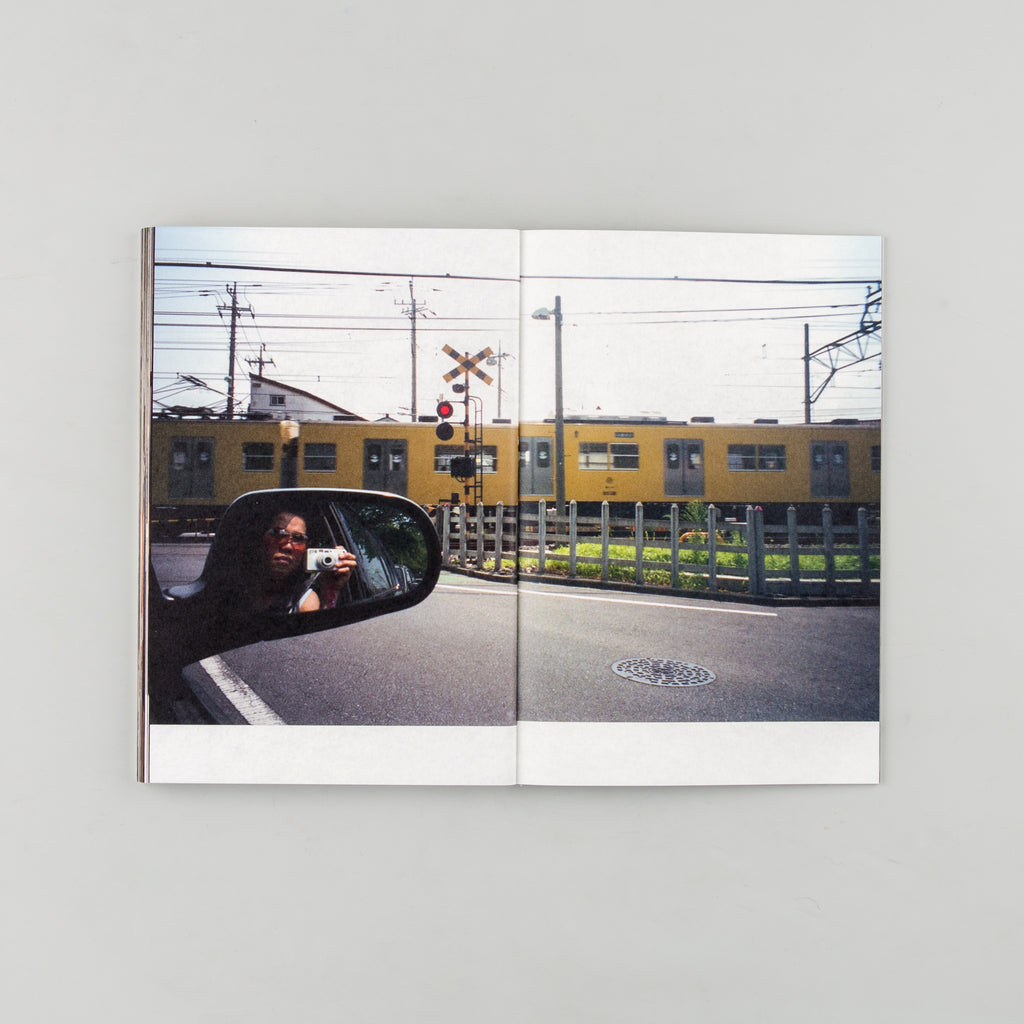

“In this book, I sequenced the images chronologically, so you can see the change. There are often reasons behind my change in camera, lens, or style of shooting. For example, I started using compact-film cameras more, right after I had a child. My subject matter is often changed by my experiences and by the social changes I experienced. I became more aware of feminist issues after having a child, and then the earthquake in 2011 made me face domestic political issues. My personal interests also changed, and aging, too, is just another cause. When I was young, I thought my body was my own property so I could do whatever, but my son changed that idea completely. I think that my photographs——both set-ups and snap shots——are quite personal.”

Translation by Akiko Ichikawa